Smashing Arrows and Bad Theology

Recently, I attended a conference where a local pastor gave a talk on living a fervent Christian life. It’s worth noting up front: this was a topical message, not an expositional sermon, and it was delivered in a conference setting, not a Sunday pulpit. I’m not critiquing the speaker personally; he’s been a tremendous blessing in my life. However, his talk illustrates a broader concern I’ve seen growing in the church, especially in the United States.

The passage in view was 2 Kings 13:14–19. The speaker interpreted King Joash’s act of striking the ground with arrows only three times instead of five or six as a caution against small prayers. The takeaway, as presented, was that we need to “pray God-sized prayers” or risk missing out on God’s best. Now, I believe in bold prayer. But this particular application is moralistic at best and deeply misleading at worst. It is part of a troubling trend: reducing rich biblical texts to vague exhortations about personal effort or spiritual intensity.

We are in an era where theology is often simplified to make room for accessibility. Beginner classes are endless, and spiritual milk is constantly on tap, but meat is scarce. This isn’t a critique of simplicity; it’s a warning against shallowness. The Protestant Reformation recovered the radical idea that ordinary believers can know God through His Word. But in our modern attempt to keep things easy and upbeat, we’ve substituted that heritage with a bland moralism, where the goal is relevance, not reverence.

The cure isn’t better illustrations or more emotional appeal. The cure is sound theology, rooted in covenant, centered in Christ, and formed by Scripture. So what actually happens in 2 Kings 13, and what does it teach us about God and ourselves?

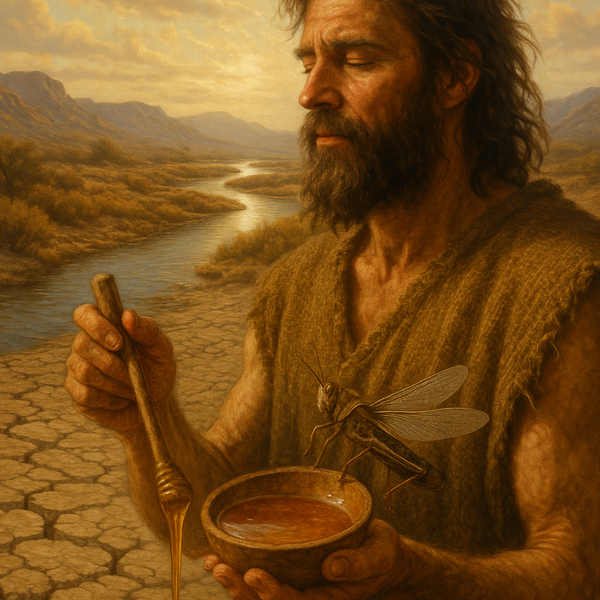

The passage unfolds in the final days of Elisha’s life. Joash, king of Israel, visits the dying prophet. He weeps over Elisha and calls him, “My father, my father! The chariots of Israel and its horsemen!” (echoing Elisha’s own words when Elijah was taken up). Elisha tells Joash to take a bow and arrows, and he places his hands on the king’s hands as Joash shoots an arrow eastward. Elisha interprets this act as “the LORD’s arrow of victory” over Syria, with a promise of triumph at Aphek. Then, Elisha tells him to strike the ground with the remaining arrows. Joash strikes three times and stops. Elisha becomes angry. Had Joash struck five or six times, Israel would have seen total victory. Instead, they will win three battles and no more.

This is not a text about “how much do you want it?” It’s not a parable about ambition. It is a prophetic sign-act. Elisha’s instructions are a symbolic oracle, a living parable meant to convey God’s covenant intentions. Joash’s response isn’t just a tactical misstep; it reveals a deeper reality. Like his forefathers, he does not walk in complete covenant obedience (2 Kings 13:11). His visit to Elisha, though emotional, is not born of repentance. He pays lip service to the prophet, but his actions betray a shallow trust in the Lord.

Elisha’s anger, then, is not over personal passion. It is a covenantal grief. Joash’s timid response mirrors Israel’s long history of half-hearted devotion. God had promised deliverance, but Joash could not or would not grasp it fully. His tepid obedience would limit the victory. Even in this, God still grants mercy. Three victories will come. Yet the partiality of the outcome is itself a judgment, just enough to show God’s faithfulness but not sufficient to remove the shadow of covenant infidelity.

This moment also signals a larger shift. Elisha dies soon after, and there is no prophetic successor. The era of Elijah and Elisha, marked by confrontation, miracles, and direct revelation, is coming to a close. The prophetic voice in the north grows quiet. The long-suffering patience of God is still evident, but His warnings are nearing completion. Grace is still offered, but judgment draws near. The tension between mercy and justice presses in.

So what does this mean for us? Not that we should pray louder or live more dramatically. The story isn’t about the size of your faith but the sufficiency of God’s grace. Joash, like every king before him, leaves us longing for a better one. A king who will not falter. A king who will not stop short. A king who will not merely strike the ground with arrows but who will strike the decisive blow against sin and death.

That King is Jesus.

Where Joash hesitates, Jesus does not. Where Israel waffles, Christ endures. He doesn’t gesture toward victory, He secures it. He obeys perfectly, suffers fully, and triumphs eternally. Elisha’s symbolic actions point ahead to Christ’s prophetic office. But Jesus doesn’t speak in signs. He is the sign. He is the Word-made flesh, the final prophet, the victorious King.

He sets His face like flint toward Jerusalem. He does not stop at three strikes. He bears the full weight of judgment, drinks the cup of wrath to the dregs, and announces, “It is finished.” In Him, salvation is not a partial promise; it is a blood-bought reality.

So no, this passage doesn’t call us to strike harder. It calls us to trust deeper. Our hope isn’t in the fervency of our striking but in the sufficiency of Christ’s finished work. Grace isn’t dangled out like a prize to the most passionate. It is secured by the King, who never faltered.